11 Museum-Worthy Scientific Instruments From the Early 1900s

When we think of museum-worthy scientific instruments from the early 1900s, we’re not just looking at old tools, we’re seeing milestones in the history of human achievement. These instruments played vital roles in the scientific breakthroughs of their time and continue to captivate us with their ingenuity. From microscopes to early calculators, each piece reflects the rapid advancements made during the early 20th century. They are preserved in museums for their cultural, historical, and educational value.

This post may contain affiliate links, which helps keep this content free. Please read our disclosure for more info.

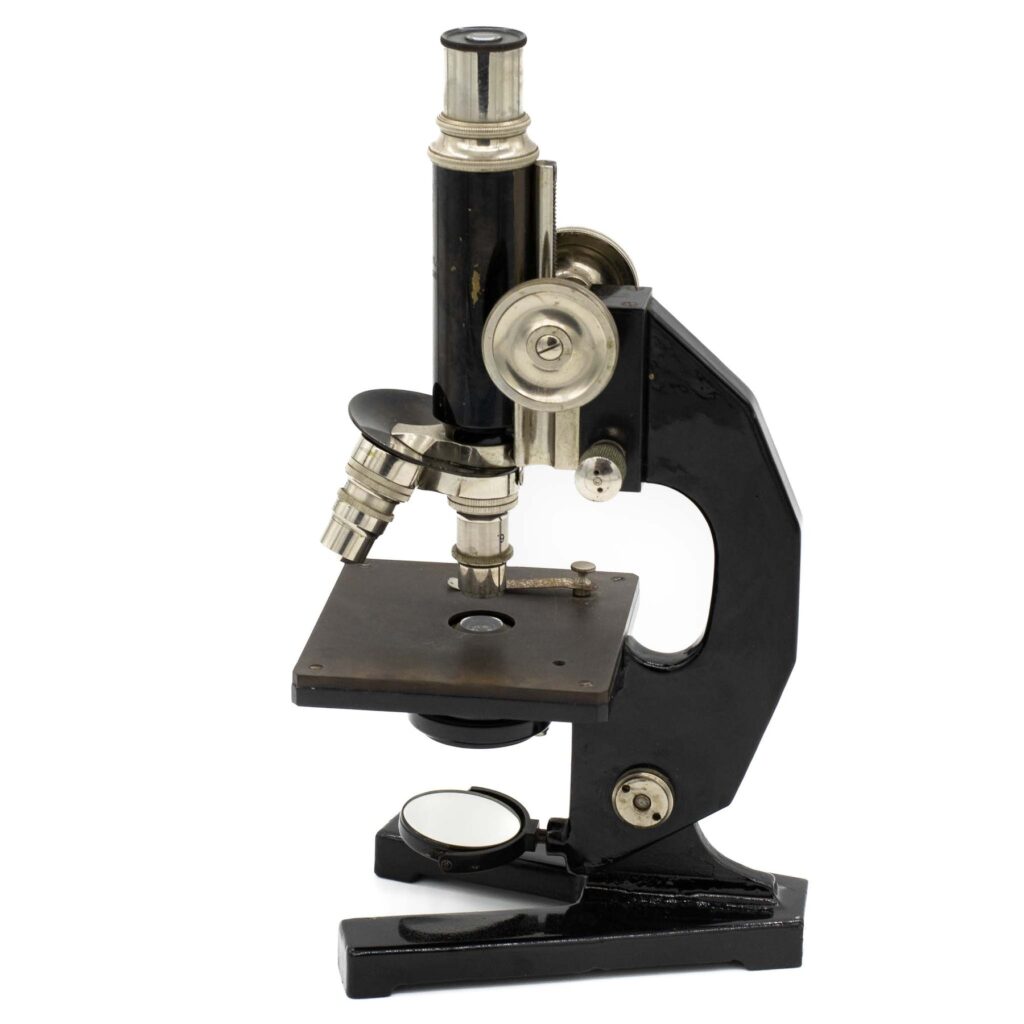

Ernst Leitz Wetzlar Microscope

This microscope, produced by the German firm Ernst Leitz Wetzlar around 1910–1915, was designed for advanced laboratory work in biology and medicine. It features high-quality brass optics and precision mechanical components, making it suited for detailed cell and tissue study. Its current market value for an intact early model in good condition is approximately $1,000 to $2,500, though provenance and factory markings can raise the amount. Because so few early 20th-century microscopes retain their original accessories it has become rare. Collectors and institutions prize it for its technological significance in microscopy.

What makes this microscope museum-worthy is the combination of fine craftsmanship, early industrial optical engineering and direct connection to a period when microscopy expanded rapidly. It reflects a time when lab science was becoming more systematic and documented. The brass body, the rack-and-pinion focus, and the original finish show quality rarely maintained in mass-produced modern instruments. Even the case and labeling are part of the story, showing how labs were set up around 1910. For a museum it offers both aesthetic appeal and genuine scientific heritage.

Saybolt Standard Universal Oil Viscosimeter

This instrument was released in 1914 and is known as the Saybolt Standard Universal Viscosimeter, used to measure the viscosity of oils and petroleum products. It works by measuring the time it takes a set volume of oil to flow through an orifice under standard temperature, making it vital for early 20th-century labs in chemistry and industry. Market listings show values in the range of $400 to $600 for working units with original parts. Its rarity results from industrial obsolescence, the replacement of oil testing methods, and many units being discarded. Its value is increased when factory markings, calibration certificate or original stand survive.

What makes this instrument museum worthy is its role in industrial science and quality control during a period of rapid growth in petroleum and lubrication technology. It reflects the science of measurement and standardization at a time when manufacturing and engineering were scaling up. The design – brass, glass, engraved scales – shows the aesthetic of laboratory equipment in the 1910s. It offers a story about how industries controlled fluid properties in the early 20th century. For a display it shows how science moved beyond pure research into industrial application.

Antique Field Telescope

This field telescope, probably manufactured around 1900–1915, was used for surveying, astronomy or military observation depending on its configuration. With brass body, draw-tube optics and adjustable tripod mount, it illustrates outdoor scientific or engineering work of that era. Intact examples can command $1,000 to $2,000, especially if maker and provenance are documented. Many units have been modified, lost parts or suffer damage from outdoor use, making fully original examples rare. The original wooden tripod or case increases value.

This item is museum-worthy because it connects to exploration, surveying, astronomy or military science around the turn of the century. It shows how scientists, engineers and observers measured and viewed the world before modern compact optics. The materials and construction reflect the portable instrument design of 1900s. It offers a tactile link to field-work of that era. For display, it can illustrate science outside the lab and the global spread of measurement tools.

Theis and Co K-G Wolzhausen Microscope

Coming from Theis and Co in Wolzhausen (Germany) around circa 1905–1910, this microscope was made for precision research, perhaps in chemistry or biology. It has a sturdy cast-iron base, fine optical components, and was part of the early wave of instruments used in university labs. An example in good cosmetic and working condition is likely valued around $800 to $1,500, depending on optics and completeness. Because many such instruments were scrapped, modified, or parts lost over time, finding a complete early example is uncommon. The maker’s reputation and regional history add to its desirability.

This instrument is museum-worthy because it represents a transitional era between handcrafted optics and more standardized laboratory equipment. It bridges the 19th-century bespoke instrument and modern mass-production. The mechanical design, heavy brass parts, and original lab markings illustrate how scientific work was done in that era. Its survival with original components provides a tangible link to the teaching labs of the early 20th century. Displaying this kind of instrument allows visitors to see how microscopy advanced and what researchers of that era worked with.

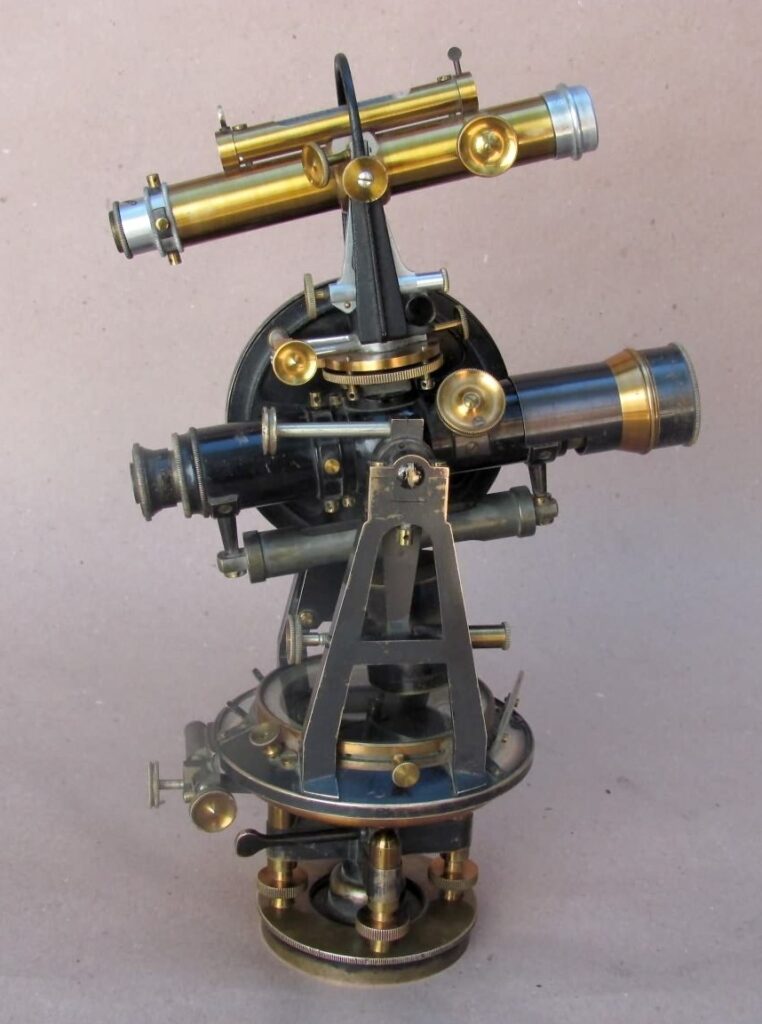

Early 20th-Century Surveyor’s Transit

This surveyor’s transit, issued around 1910–1915, was used for land measurement, mapping and civil engineering, featuring a rotating telescope, leveling screws, and angular scales. It was an essential tool in building infrastructure like roads, railways and cities. A well-preserved example might sell for $900 to $1,500, depending on maker, case, and condition. Many were heavily used in the field and lost their cases or markings, so intact specimens are uncommon. Original accessories such as plumb bob, case, and tripod add interest.

The museum potential of this instrument lies in its representation of how physical space was measured and shaped in the early 20th century. It shows the link between science, engineering and the built environment. The precision workmanship, brass finish and engraved scales reflect the era’s instrument-making standards. It also tells a story about surveying and mapping before electronic positioning systems. As a display piece, it bridges science and infrastructure.

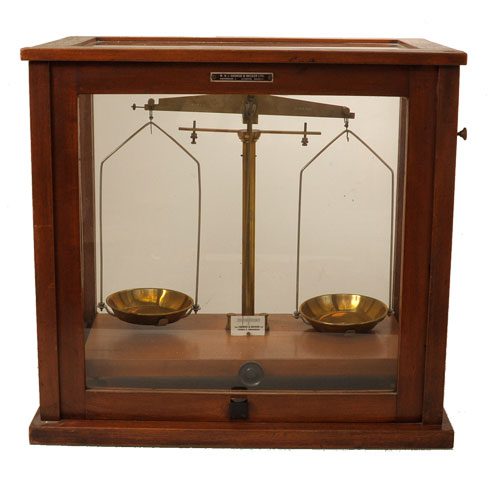

Early 1900s Analytical Balance

Introduced around 1912, this analytical balance was used in chemistry labs for precisely weighing minute quantities of substances. It features a beam, sliding weights, enclosed glass case and fine leveling screws. In good working condition with original pan and glass enclosure, one might find values near $600 to $1,200. Many have lost their enclosures, suffered scale damage or been repurposed, reducing surviving numbers. Collectors and institutions value original manufacturer labels and calibration plates.

Its museum-worthiness comes from its role in lab science where precise measurement underpinned chemistry, pharmaceuticals and research around that time. It reflects the craftsmanship of instrument making and the standards of measurement before digital balances. The clear glass case and polished metal make it visually appealing and instructive. It links to themes of quantification, science education and industrial chemistry in the early 1900s. As a display item it brings laboratory history to life.

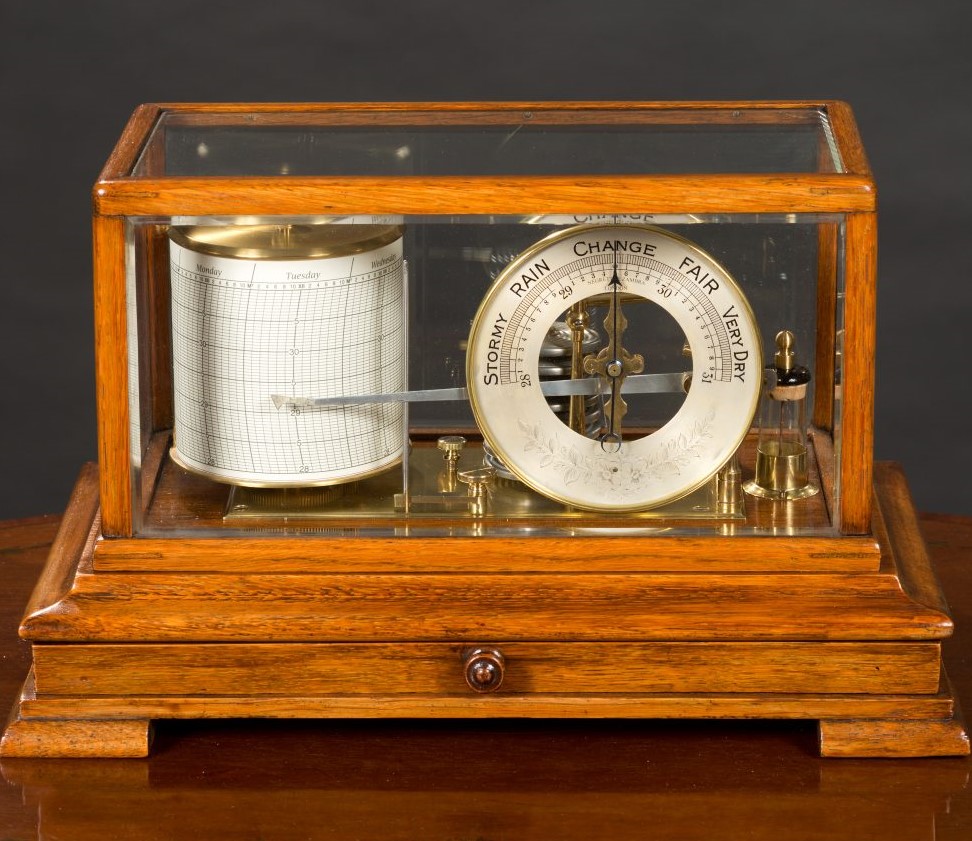

Early 20th-Century Barograph

This barograph from around 1905 recorded atmospheric pressure over time on a drum chart, used in weather stations or shipping. It comprises brass mechanism, small clockwork motor, and a paper chart drum, enclosed in mahogany or brass case. An example with original chart paper and case might be valued around $400 to $800. Many were discarded or altered when modern electronic recording devices replaced them, making well-preserved units uncommon. The maker’s mark and complete movement enhance its appeal.

What gives it museum status is how it illustrates early instrumentation of meteorology and the recording of environmental data. It captures a moment when scientists began to log and analyse weather patterns. The visual of the moving pen arm and paper chart adds dynamic interest for exhibit. It pairs aesthetics with functionality, showing how data was captured mechanically. For display it connects science, weather and instrumentation history.

Early 1900s Polarimeter

A polarimeter built around 1915 measured optical rotation of substances, commonly used in sugar, pharmaceutical or chemical industries. It contains a light source, polarising filters, sample tube and scale, all mounted in a precision instrument housing. Surviving models in good condition might be valued around $800 to $1,500, depending on maker and completeness. Many units were used in industrial settings, had parts replaced or were scrapped, so original intact examples are rarer. Original manufacturer certificate or case further raises value.

Its significance and museum appeal lie in its central role in analytical chemistry and industry in the early 20th century. It shows how scientists measured properties of substances in a way that linked laboratory work and industrial quality control. The instrument’s polished optics, precision dial and age-patina tell the story of early measurement science. It serves an educational purpose by showing how measurement standards developed over time. As a display piece it combines history, science and design from the early 1900s.

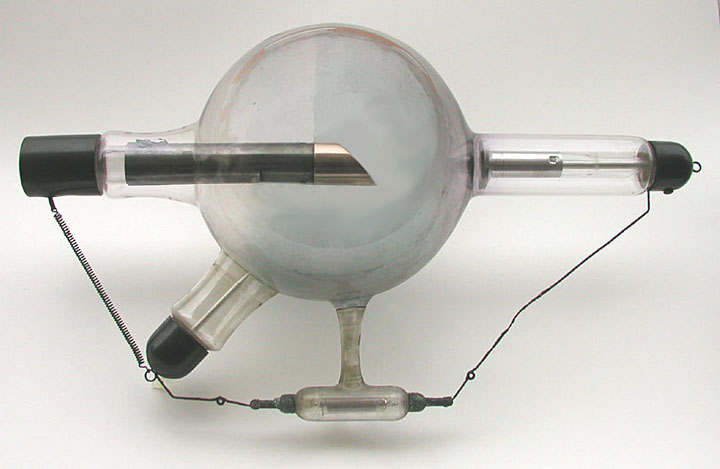

Geiger-Muller Counter

This Geiger-Muller counter, dating to around 1920, was used for detecting and measuring ionizing radiation in early radiological research and nuclear physics. It features a cylindrical tube, simple electronics and analog read-out scale designed at a time when radiation science was advancing rapidly. A well-preserved example in original condition may fetch around $1,200 to $2,000, depending on manufacturer, calibration plate and completeness. Many units from that era were dismantled, modified or lost their recording parts, which makes intact originals rare. The instrument also carries the story of how scientific safety and measurement techniques matured in the early 20th century.

What gives this counter its museum appeal is the tangible link to early nuclear and radiological science, a field that shaped major scientific and historical events. The brass and glass components, wiring and analog meter reflect a hands-on era of experimentation before digital electronics. Seeing the original tube, controls and labels helps viewers understand how scientists tracked radiation levels at a time when the risks and mechanisms were still being uncovered. This item serves both as a technological artifact and a narrative piece about scientific discovery and caution. In a display it bridges fields like physics, medicine and history of science.

Wireless Telegraphy Spark Gap Transmitter

Around the year 1912, spark gap transmitters were employed in wireless telegraphy systems for maritime and military communications. This particular piece features a spark gap assembly, condenser, induction coil and early wiring mounted on a wooden base, typical of pre-World War I radio technology. Collectors of telecommunications and scientific devices list intact examples with original spark gap hardware and labels in the range of $700 to $1,300. Many were scrapped or repurposed as vacuum tube technology replaced them, reducing the number of surviving original units. This transmitter marks a pivot point in communication science when wireless signals began to travel farther and faster than ever before.

Its appeal for museum display lies in showcasing the early wireless era when physics, engineering and global communications converged. The visible spark gap, heavy coil, and insulators tell a story of electrical experimentation and global connectivity. The piece invites viewers to reflect on the early wireless world, including maritime safety, radio pioneers and wartime signalling. Its tangible presence makes the transition from wired telegraphy to wireless real and accessible. As an exhibit object it helps link technical science to societal change and global history.

Early 1900s X-Ray Tube and Housing Assembly

This X-ray tube and housing assembly, produced around 1915, was used in medical and industrial imaging in the early 20th century, shortly after the discovery of X-rays. The unit typically includes a glass tube, high-voltage connector, shielding housing, and control console or meter. A unit in complete and good condition might command $1,500 to $3,000, especially if marked by an early manufacturer and accompanied by original accessories. Many tubes broke, were replaced, or discarded once more modern designs emerged, which contributes to its rarity. It represents a major step in diagnostic and scientific imagery when humans first saw inside bodies, materials and structures using invisible rays.

What makes this object museum-worthy is that it sits at the intersection of physics, medicine and industrial inspection, capturing a key moment in science and technology. The glass tube and high-voltage wiring evoke the risk-laden, pioneering phase of imaging science, when experimenters handled high voltages and radiation. In a display it conveys the ingenuity, caution and change that radiology brought into healthcare and industry. It helps visitors see how early scientists and doctors managed new scientific powers and their implications. As such it stands as a symbol of early 20th-century scientific ambition and technical progress.

This article originally appeared on Avocadu.